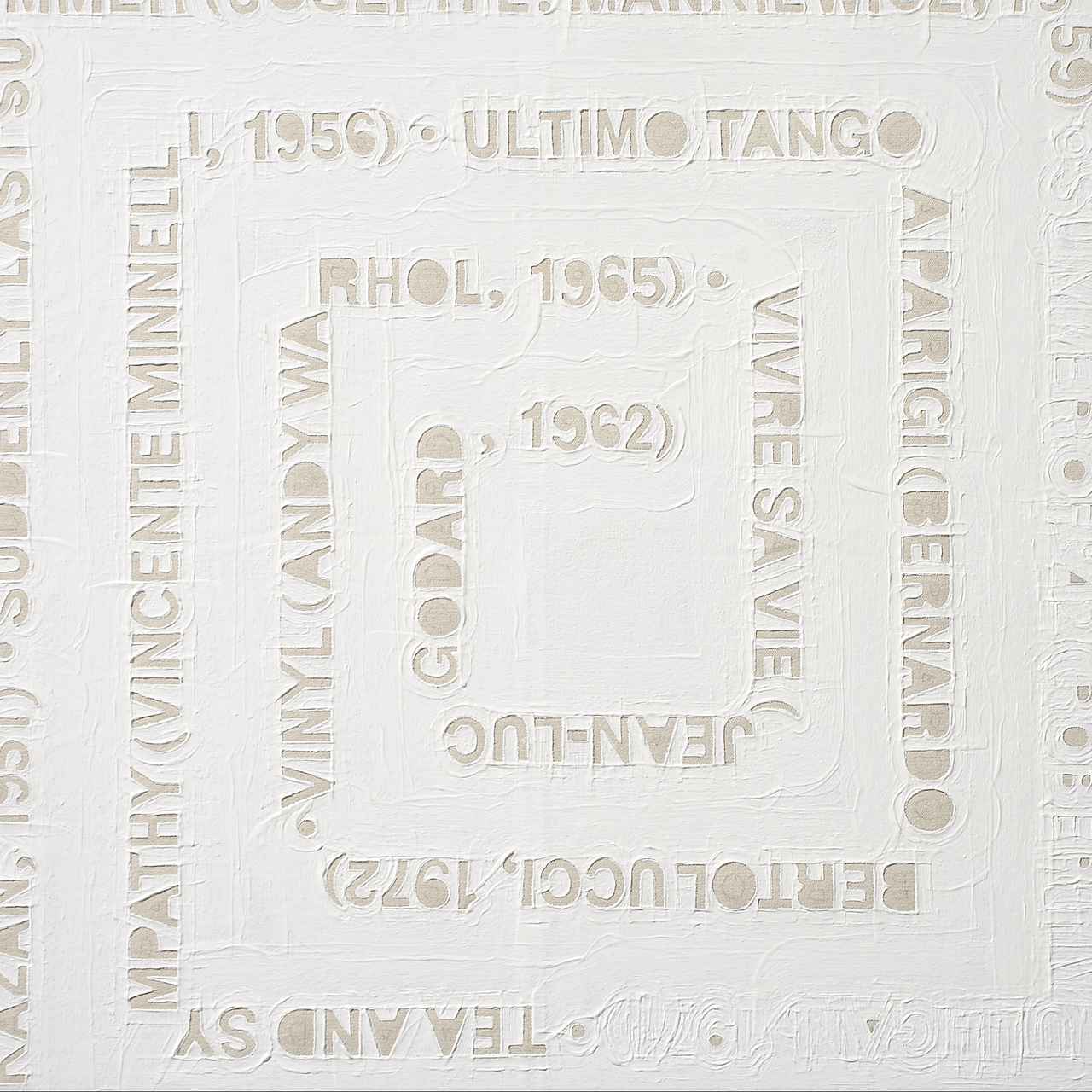

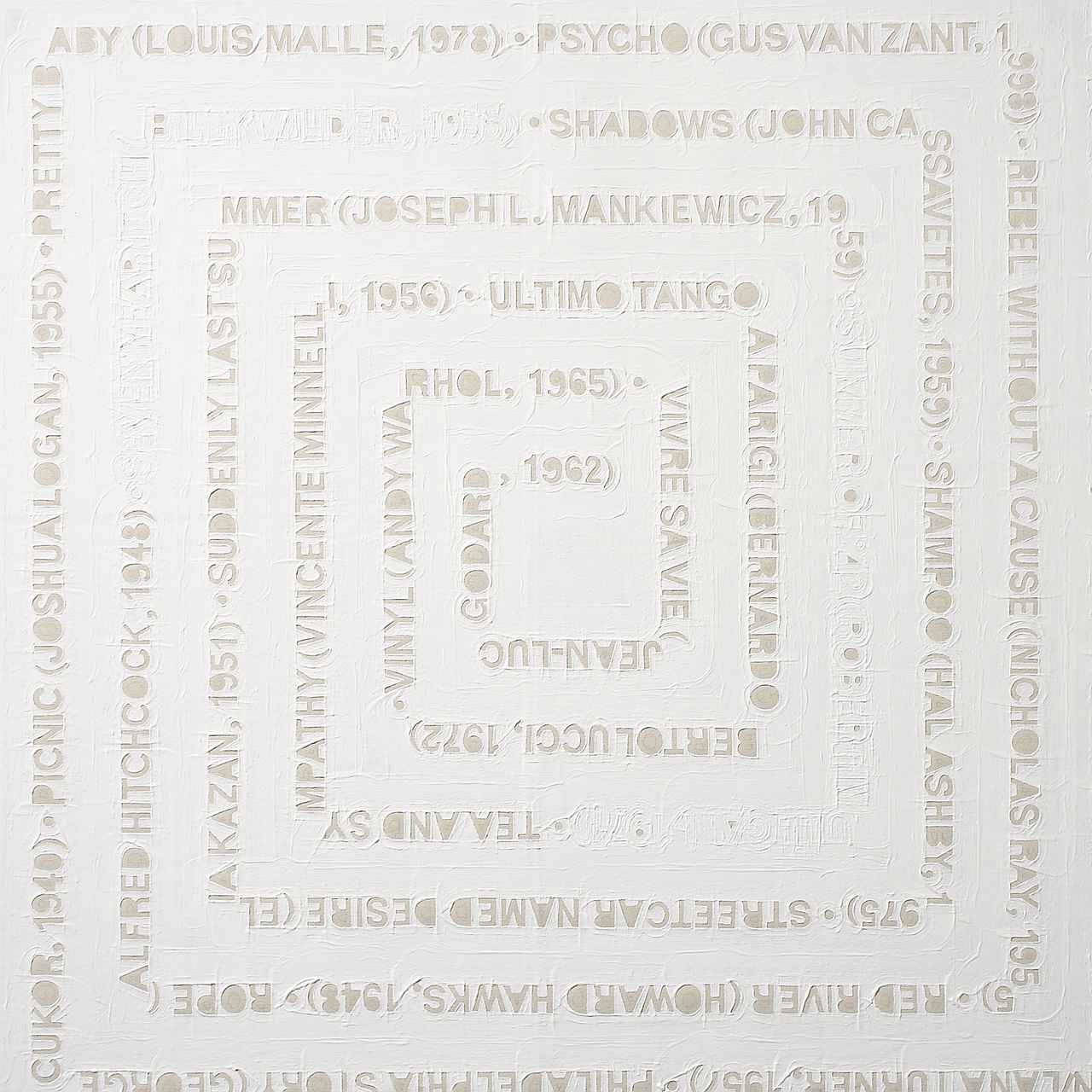

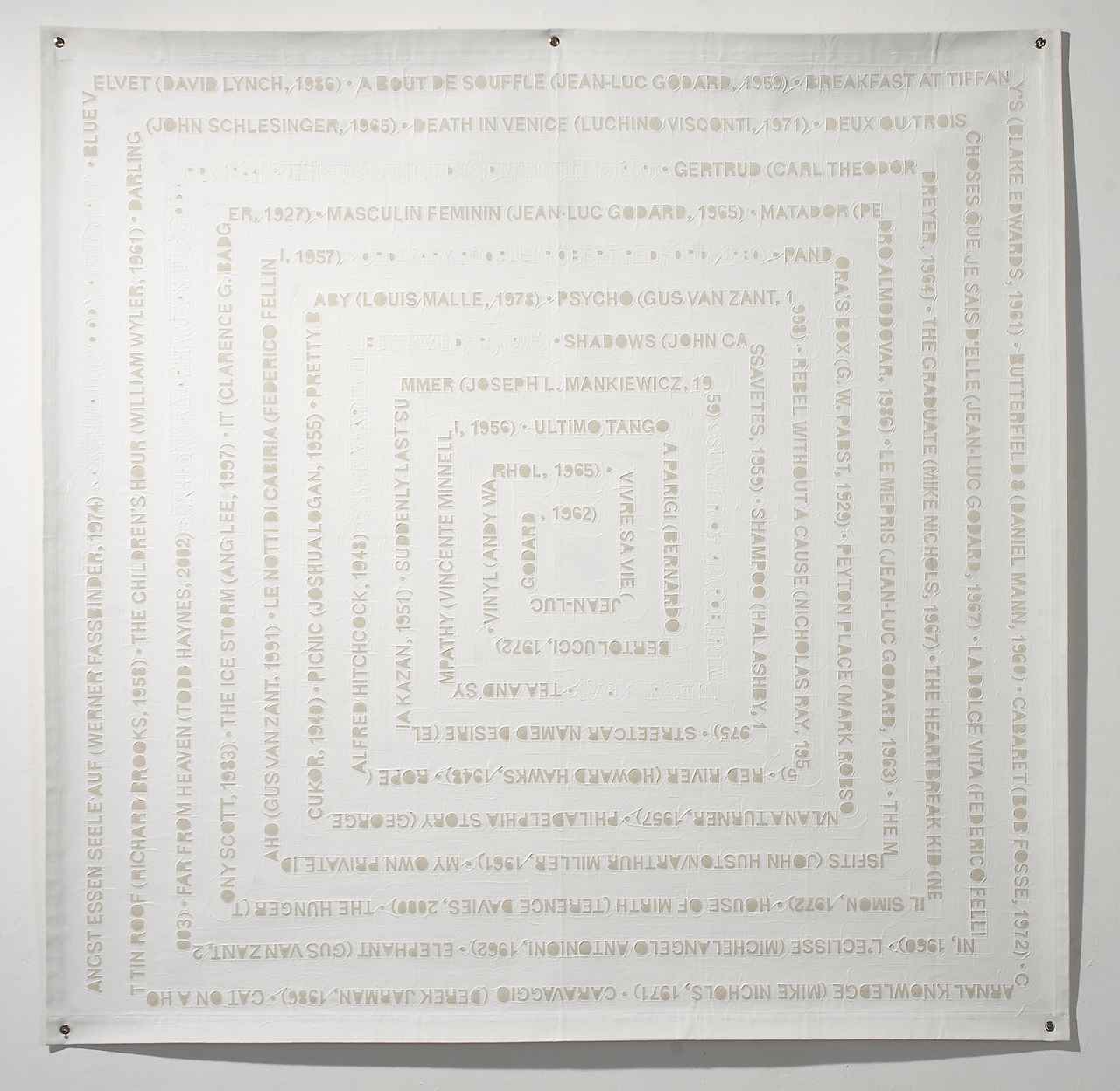

what sexual revolution? pits the banality of monochromatic painting against a sculptural structure, flicker film, and an anecdote about early childhood experience with modern art. The two sections of this structure are joined together at a wide angle, like an open book. With systematically painted marks of gesso built up after many coats, the canvas ‘movie poster’ on the right section lists some fifty films from memory. Replicating the split-second aspect of visual memory, the flicker film/video projected onto the left section uses about five-hundred stills (shown over the course of 3 minutes), which were taken from the films listed in the poster. The entire composite attempts to make montage physical: where each form employed cancels out the context of the other, to develop a continuous trans-modal experience. Behind the ‘movie poster’ hangs an anecdote in mirrored vinyl, which reflects reading viewers. Written in the first person, it tells of a memory that informs how pop culture is bound up with high art.

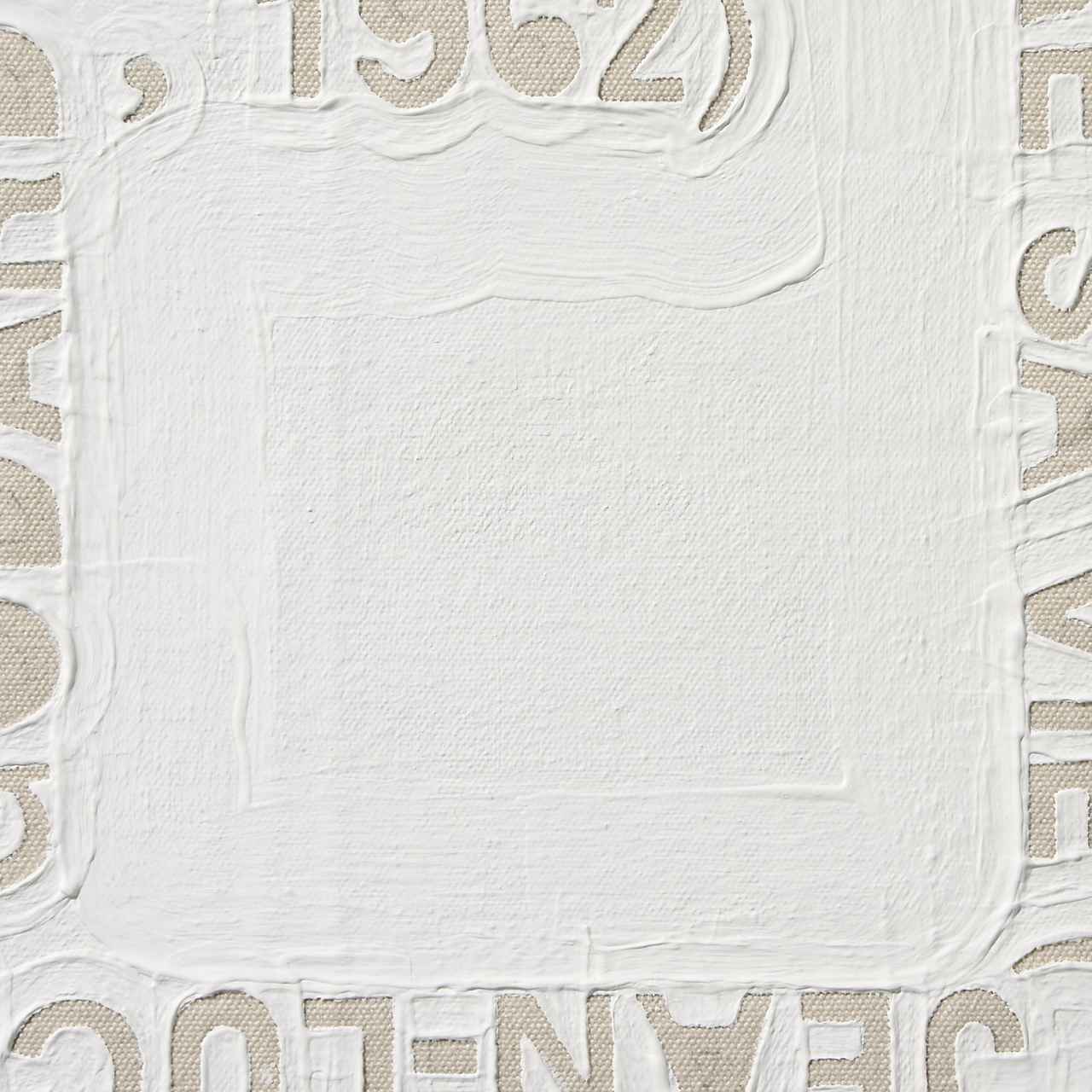

The film titles in the ‘movie poster’ are in alphabetical (arbitrary) order, beginning with the edges of the canvas and working inward. Some film titles from the early painting of the list are systematically erased: letters painted out from their interior with a reverse logic that formed the letters. Each mark is building up a surface that points out the structure of marks that came together to form the letters, then words, and then the ‘whole’ or continuous design. Many, many layers of gestural marks were required to bridge the area between the linear, time-based nature of text and the immediate, spatial nature of visual abstraction.

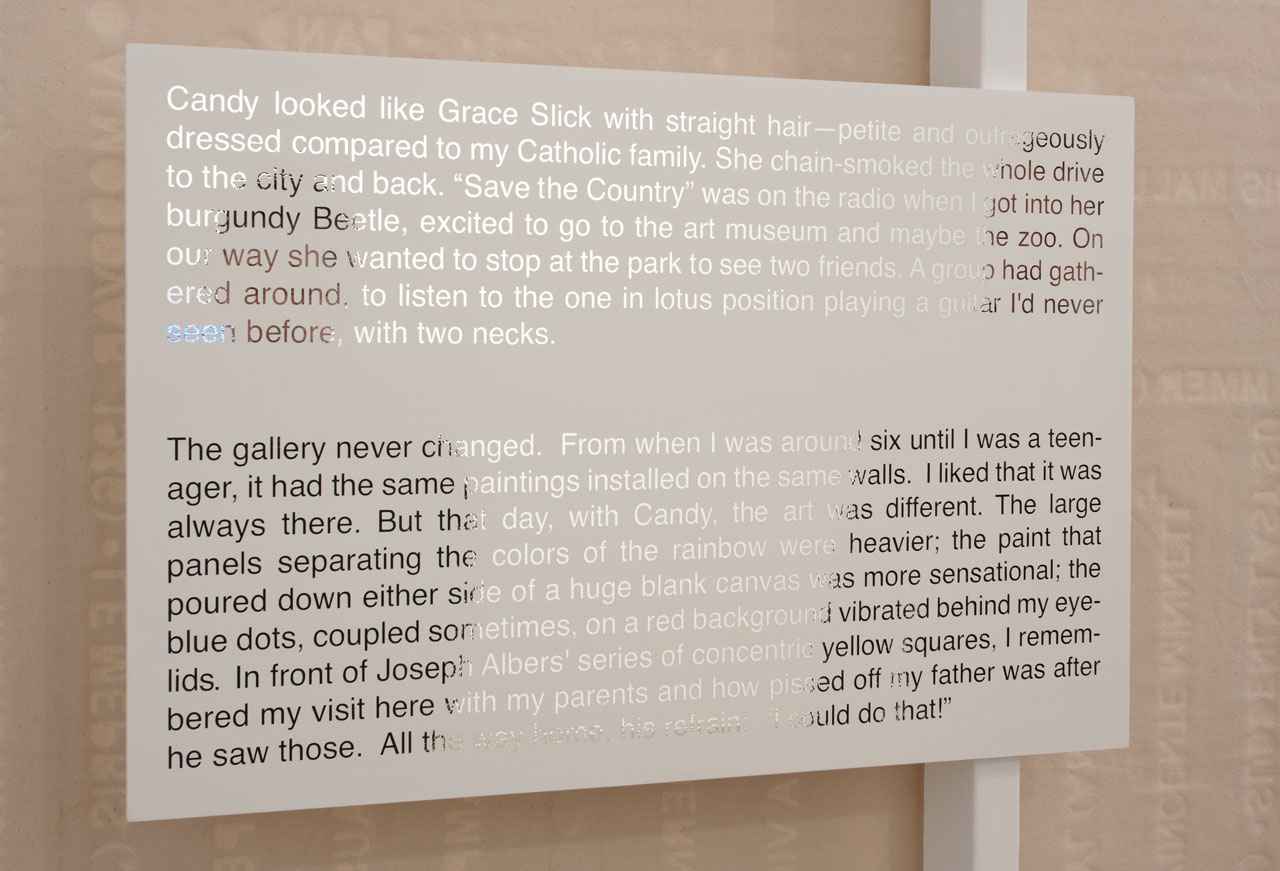

Candy looked like Grace Slick with straight hair—petite and outrageously dressed compared to my Catholic family. She chain-smoked the whole drive to the city and back. “Save the Country” was on the radio when I got into her burgundy Beetle, excited to go to the art museum and maybe the zoo. On our way she wanted to stop at the park to see two friends. A group had gathered around, to listen to the one in lotus position playing a guitar I'd never seen before, with two necks.

The gallery never changed. From when I was around six until I was a teenager, it had the same paintings installed on the same walls. I liked that it was always there. But that day, with Candy, the art was different. The large panels separating the colors of the rainbow were heavier; the paint that poured down either side of a huge blank canvas was more sensational; the blue dots, coupled sometimes, on a red background vibrated behind my eyelids. In front of Joseph Albers' series of concentric yellow squares, I remembered my visit here with my parents and how pissed off my father was after he saw those. All the way home, his refrain: “I could do that!”